“The job of the artist is always to deepen the mystery.”

– Francis Bacon –

Who is Francis Bacon?

Francis Bacon (1909–1992) is widely recognized as one of the most powerful and original figures in modern art. His works, characterized by their raw emotion, distortion of the human figure, and intense exploration of the human psyche, have had a lasting impact on the art world. Bacon’s paintings often evoke feelings of violence, alienation, sexuality, and psychological trauma. The themes of rebellion and sexuality, particularly in the context of his own homosexuality, are central to understanding his art. Additionally, Bacon’s work draws on elements of the scream, not just as a symbol of existential angst, but as a raw, physical representation of suffering and despair

Bacon’s Early Life: Rebellion and Repression

Francis Bacon was born in Dublin, Ireland, into a strict Anglo-Irish family. His father, Edward Bacon, was a retired British army officer known for his harshness and authoritarian manner. Bacon’s mother, Christina, was a more nurturing presence, though the family dynamic was often marked by tension. Bacon’s early life was marked by conflict, both at home and in the world around him. From a young age, he was aware of his homosexuality, but at that time, homosexuality was heavily stigmatized and criminalized. This created an atmosphere of fear, shame, and repression that would haunt Bacon throughout his life.

Bacon’s rebellion against his family and society was evident early on. His father disapproved of his son’s growing interest in art and, particularly, his sexual orientation. Bacon’s sexuality was a source of intense inner conflict, and his rebellion was not only against the societal values that rejected him but also against the expectations placed on him by his family. At the age of 16, following a series of violent clashes with his father, Bacon left home and relocated to London. This decision was an act of defiance—Bacon sought to break free from the constraints of family and society and to live as his authentic self, despite the risks involved.

Bacon’s relationship with his father remained strained throughout his life, and it is clear that the trauma of his family’s rejection played a crucial role in his artistic development. His works, which are often filled with images of isolation, anguish, and psychological fragmentation, can be seen as a direct response to these early experiences of repression and conflict. Bacon’s rebellion against both his familial authority and the broader societal structures of his time would shape the themes and aesthetics of his later works.

Sexuality: The Core of Bacon’s Artistic Struggle

Bacon’s homosexuality was not merely a personal aspect of his life—it was a central theme of his art. Living as a gay man in the first half of the 20th century, when homosexuality was criminalized and socially ostracized, Bacon’s art can be seen as both an expression of sexual identity and an act of defiance against societal norms. His works often grapple with themes of sexual violence, alienation, repression, and the psychological toll of living in a world that rejected his desires.

Much of Bacon’s early work reflects his inner turmoil and sexual frustration. His paintings, especially those of the 1940s and 1950s, often depict distorted, contorted bodies locked in moments of anguish and despair. These figures, which are frequently male, seem trapped in a state of psychological agony that mirrors Bacon’s own emotional pain. His most famous works, such as the Triptychs and the Pope Series, often feature figures that appear distorted, fragmented, or caught in moments of sexual violence and disintegration.

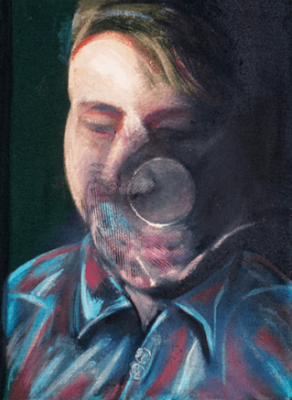

Bacon’s relationship with George Dyer, a former criminal and lover, was pivotal in the artist’s exploration of sexuality and its connection to violence and self-doubt. Dyer served as both a lover and a muse for many of Bacon’s most famous works, including Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror (1968). In this painting, Dyer’s image is reflected in a mirror, but the reflection is distorted, evoking a sense of emotional and psychological fragmentation. The figure seems trapped in a moment of intense existential struggle, perhaps symbolizing the conflict between identity and desire.

In works like Triptych May-June (1973), Bacon explores the emotional and psychological complexities of desire, using his figures to symbolize the destructive power of passion. The figures in these paintings are viscerally disfigured, caught between states of physical and emotional collapse. These figures do not conform to traditional ideals of beauty or sexual attraction; instead, they embody the chaos and torment that often accompany the struggle for intimacy and self-acceptance.

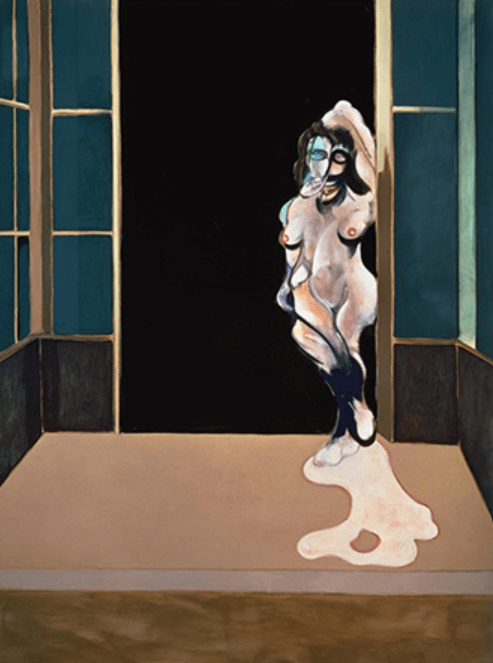

Bacon’s works, in many ways, present a rebellion against traditional representations of beauty, sexual norms, and the boundaries of the human body. By distorting and fragmenting the human form, Bacon sought to represent a more truthful vision of the human experience—one that is marked by vulnerability, desire, and violence. In this sense, his art is both a protest against conventional representations of the human figure and an exploration of the psychological and emotional struggles inherent in the experience of being an outsider in a repressive society.

The Scream: Echoes of Munch and Bacon’s Psychological Expressionism

One of the most striking aspects of Bacon’s work is his use of the scream, both as a literal and metaphorical expression of anguish, emotional distress, and existential horror. The figure of the scream—best exemplified in Edvard Munch’s iconic The Scream (1893)—represents the primal, visceral cry of a human being overwhelmed by fear, isolation, and despair. Bacon, though, did not simply echo Munch’s imagery; he reinterpreted the scream as a means of exploring psychological fragmentation and the violence inherent in the human condition.

Bacon’s works, especially his Pope series and his triptychs, often depict figures whose mouths are open in what appears to be a scream, or figures whose faces are twisted in expressions of intense psychological distress. This screaming figure is not just a literal cry for help, but a metaphor for the internal breakdown of the human psyche. These figures are trapped in a state of psychic violence, as if their bodies themselves are breaking down in response to the trauma and anguish they have endured.

In Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953), for example, the Pope is depicted with an agonized expression, his mouth open in a silent scream. The figure is caged in a distorted space that reflects the power dynamics at play within the image. Here, Bacon uses the figure of the Pope—a symbol of religious and institutional authority—to explore the psychological violence that accompanies the repression of the self. The Pope’s scream is not just about religious or political authority, but about the anguish that comes from being trapped in a system that dehumanizes and oppresses individuals

In contrast to Munch’s figure, which seems to scream outward into the world, Bacon’s figures seem to scream inward, trapped in the emotional and psychological chaos of their own minds. The scream in Bacon’s work is a private scream, one that is internalized and fragmented, reflecting the artist’s own sense of alienation and his rejection of societal constraints.

Bacon’s use of the scream also speaks to the violence that is often associated with his depictions of the human body. The scream is not merely a sound but a physical manifestation of inner turmoil, a reflection of the violent internal struggle of being a human being trapped in a fragile, decaying body.

Art as Rebellion: Bacon’s Defiance of Convention

Bacon’s art is a rebellion not just against his family and society but against the traditional conventions of art itself. Bacon rejected the idea of idealized beauty and harmony, opting instead to depict the human body in its most raw, grotesque, and vulnerable form. His figures are distorted, fragmented, and often appear to be in a state of collapse. This rejection of the classical idea of beauty is part of Bacon’s broader rebellion against the norms and expectations of both society and the art world.

In works such as Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), Bacon presents figures that are not just distorted but also trapped in violent, psychological states. These figures seem to embody the emotional and psychological disintegration that is central to Bacon’s worldview. His rejection of beauty is also a rejection of the idea that the human body should be idealized or portrayed as something untouched by suffering. Instead, Bacon’s art suggests that the truth of human existence lies in its vulnerability and fragility.

Bacon’s rebellion also extended to his approach to painting itself. He was uninterested in the clean lines and precision of classical painting. Instead, he used a bold, gestural style, often applying paint in thick, expressive layers.