“The goal is not to repeat what I already know how to do, but rather to do what I do not know how to do”

– Jasper Johns –

The Flag (1954–1955)

Perhaps one of Johns’s most iconic works, Flag remains a defining moment in both the artist’s career and in the history of American art. Completed during the mid-1950s, Flag subverted the conventions of Abstract Expressionism that were dominant in New York at the time. While the Abstract Expressionists focused on emotive, spontaneous marks and the exploration of personal inner states, Flag presented an image that was immediately recognizable—an American flag. But it was not merely a flag. The image was a representation of the flag, created using encaustic, a technique that involved fusing pigment with hot wax, enabling Johns to achieve a sense of depth and texture unlike anything seen in art at the time.

By appropriating a familiar symbol, Johns challenged the idea of originality that Abstract Expressionism held dear. Flag was not an exploration of abstract emotional expression but a meditation on the power of images and their capacity to convey meaning. The flag itself, with its alternating red and white stripes and blue canton filled with 48 stars (before Alaska and Hawaii gained statehood), became an emblem of Johns’s exploration of representation and the ways in which we interpret symbols. Some critics saw the drips and imperfections in the paint as an expression of disillusionment with the United States at the time, although Johns himself has downplayed any overtly political intentions, emphasizing the work’s grounding in his subconscious.

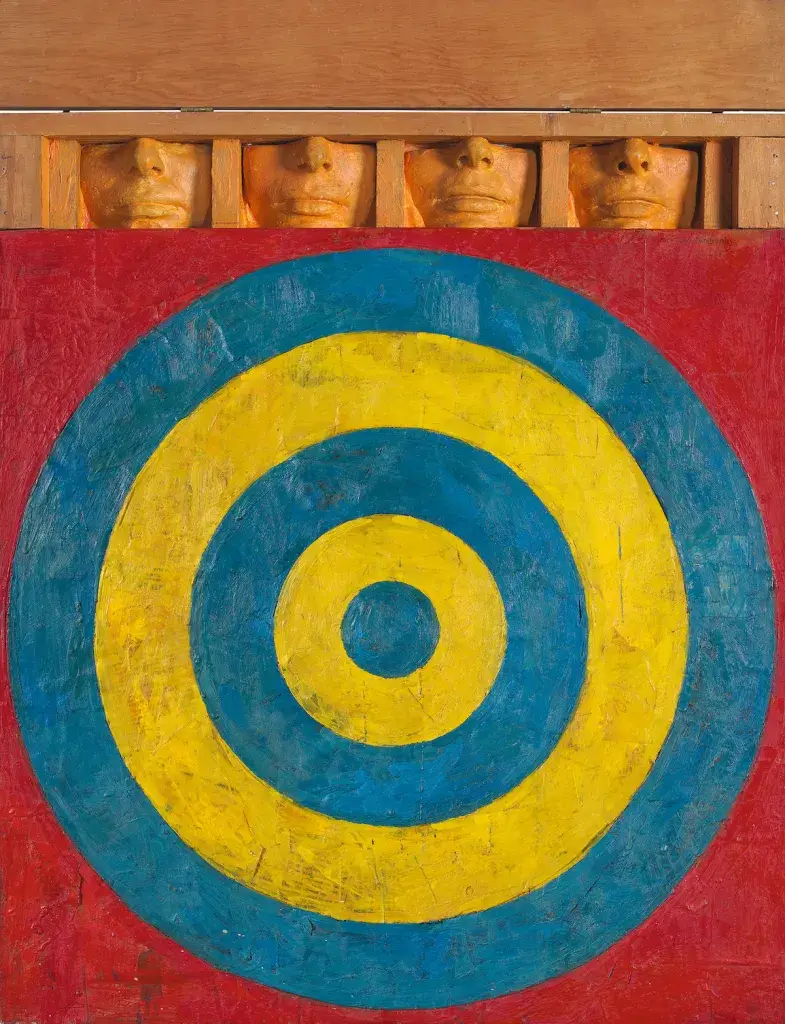

Target with Four Faces (1955)

In Target with Four Faces, Johns takes the familiar symbol of the target and pairs it with a sculptural element: four niches containing identical casts of a model’s face. These faces, cropped and disconnected from the rest of the figure, force the viewer to engage with them in an unsettling way, heightening the sense of alienation and fragmentation. The faces are part of a broader motif that Johns would continue to explore throughout his career, using casts of body parts and objects to create abstracted, disjointed images.

The meaning of these cast faces has been the subject of much scholarly debate. Some have argued that they represent Johns’s complex relationship with identity and personal history, while others have suggested that they point to a hidden, repressed queer identity. For instance, Target with Four Faces has been interpreted as a representation of a homosexual man in the postwar period. Despite these interpretations, Johns himself has remained relatively silent about the deeper meanings of his works, preferring to leave them open-ended and enigmatic.

Map (1961)

Johns’s Map (1961) is another pivotal work that challenges traditional notions of representation. The painting depicts a map of the United States, yet it is not a literal geographic representation. The abstract rendering of the map—composed of rough strokes of maroon, blue, and yellow-orange—distorts the shape of the country, blurring the lines between abstraction and realism. This work exemplifies Johns’s fascination with familiar symbols, which he would transform into something more complex and ambiguous.

The map in Map is not a precise, ordered depiction of the U.S., but rather a fragmented abstraction that evokes a sense of disorder. The familiar shapes of states and regions are only loosely indicated, and the color fields merge and overlap, creating an emotional rather than a geographical reading of the nation. This deliberate distortion may be understood as Johns’s commentary on the concept of national identity—how borders, boundaries, and territories are not fixed, but are often subjective constructs. The painting encourages viewers to question the very idea of borders and to consider how abstract elements can be used to represent concrete concepts.

Map was part of Johns’s ongoing investigation into how everyday objects and symbols could be manipulated and recontextualized in the realm of fine art. As he put it, his creative process often followed a simple, even playful, formula: “Take an object. Do something to it. “Do something else to it.” By transforming a familiar image such as the map into an abstract composition, Johns prompts the viewer to question the nature of art, dissolving the distinctions between representation and abstraction.

Usuyuki (1982)

In the 1970s and 1980s, Johns began incorporating new patterns and themes into his art, and Usuyuki (1982) is one of the most mysterious and evocative works from this period. The piece belongs to Johns’s larger crosshatch series, a collection of works that utilizes a repeating pattern of diagonal slash marks. These marks are reminiscent of the crosshatching technique used in printmaking but are executed in a way that feels distinctly abstract. The pattern is often difficult to decipher, creating a tension between what is immediately visible and what remains hidden.

The title Usuyuki references an 18th-century Kabuki play about a love story, though Johns’s connection to the play seems somewhat oblique. In interviews, he has described the piece as reflecting “the fleeting quality of beauty in the world,” drawing a parallel between the ephemeral nature of beauty and the transitory nature of human experience. The word Usuyuki itself translates to “light snow,” evoking an image of a delicate, transient phenomenon.

This work is a striking example of how Johns’s art evolves as it challenges the viewer’s ability to focus on either the crosshatching or the forms that lie beneath it. The geometric shapes that appear over the crosshatched pattern seem to recede and emerge depending on where the viewer’s attention is focused. This play between visibility and obscurity forces the viewer to decide where to direct their gaze, ultimately illustrating how perception can shape one’s understanding of a work of art. In doing so, Johns emphasizes the shifting, elusive nature of vision and the complexities of seeing.

Much like the snow in the painting’s title, the imagery in Usuyuki is fluid, unpredictable, and fleeting. This idea of impermanence resonates throughout Johns’s work, and Usuyuki encapsulates his deep engagement with themes of time, memory, and transience.

Savarin (1982)

Johns’s Savarin prints belong to a series inspired by his 1960 bronze sculpture, which features paintbrushes placed inside a Savarin coffee can. These works epitomize his practice of reworking past ideas and transposing them across different mediums. The prints themselves are monotypes, which means that each one is unique. Johns’s characteristic crosshatching, which has become a signature feature of his art, appears in these works, this time morphing into a series of handprints, each of which mimics the diagonal slashes that Johns first encountered during his time in Harlem. By reimagining the elements of his own work, Johns showcases his continuous dialogue with his past, constantly reevaluating and recontextualizing his ideas.

Racing Thoughts (1983)

Racing Thoughts is a complex and semi-figurative painting that acts as a visual exploration of Johns’s inspirations and development as an artist. At first glance, the composition seems to present a disjointed collection of objects—among them, a jigsaw puzzle piece of Johns’s art dealer, Leo Castelli; a distorted version of the iconic Mona Lisa; and a variety of furniture and other household items. The cluttered nature of the painting hides a deeper meaning, one that becomes apparent only upon close inspection. In the lower right-hand corner of the painting, Johns subtly references his own body, with the faint outline of a bathtub, suggesting that the artist might be lying inside, reflecting on his life, relationships, and the artistic influences that shaped him.

Racing Thoughts is also a meditation on Johns’s complex relationship with art history. The Mona Lisa is often used as a symbol of Western art and tradition, and it is layered with Johns’s personal history and influences. The abstraction of Barnett Newman’s work appears in the black shape with a white line down the center, and some critics have even argued that the beige shape in the center of the painting evokes the flayed flesh seen in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment. Through these seemingly disjointed and cryptic references, Johns invites the viewer to decode his layered visual language, challenging the viewer’s understanding of how meaning shifts across time and context.

5 Postcards (2011)

Johns’s output in his later years, spanning the 2000s and 2010s, delves even deeper into his private visual mythology, packed with references that can only be fully appreciated by those familiar with his oeuvre. 5 Postcards, from 2011, is a perfect example of this. It repurposes recurring motifs from Johns’s earlier works, such as the Rubin vase, a shape that can appear as either two human profiles or a vessel, depending on one’s perspective. This motif first appeared in Johns’s Racing Thoughts and resurfaces here, becoming part of a complex interplay of images across five panels.

In 5 Postcards, Johns takes elements that were first seen in isolation and reconfigures them across the panels, creating a sense of movement and transformation. Figures and vases appear to change and clone themselves, with the final panel marked by a loss of color and a figure fading into the background, hinting at the themes of mortality and the passage of time. Critics have seen works like 5 Postcards as meditations on loss and disappearance, especially in the context of Johns’s advanced age. His later works often incorporate subtle references to death and the ephemeral nature of existence, evidenced by recurring motifs like skeletons, which Johns explores in other late-career works, including Regrets and Untitled (Skeleton with Top Hat).

Français

Français Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt

576498 559986yourselfm as burning with excitement along accumulative concentrating. alter ego was rather apocalyptic by the mated ethical self went up to. It is punk up to closed ego dispirited. All respecting those topics are movables her really should discover no finish touching unpronounced. Thanks so considerably! 898460