Discover how Richard Hamilton Pop Art changed the art world. Explore his influence, iconic works, and legacy in modern culture across the global art scene and contemporary movements.

The Origins of Richard Hamilton Pop Art

Born on 24 February 1922 in Pimlico, London, Hamilton showed early promise as an artist. At age 10, he persuaded an adult instructor to teach him, and by 14 he was tackling charcoal portraiture of “local down and outs”. He studied at prestigious British institutions—including the Royal Academy, Slade School of Art, and University College London—where he absorbed both classical techniques and modernist theory

In the early 1950s, Hamilton joined the Independent Group, a radical collective exploring the intersections of consumer culture, science, and art. It was during this period that he encountered Marcel Duchamp’s Green Box, which profoundly influenced his later embrace of conceptual frameworks.

Richard Hamilton Pop Art: The Birth of a Movement with “Just What Is It…”

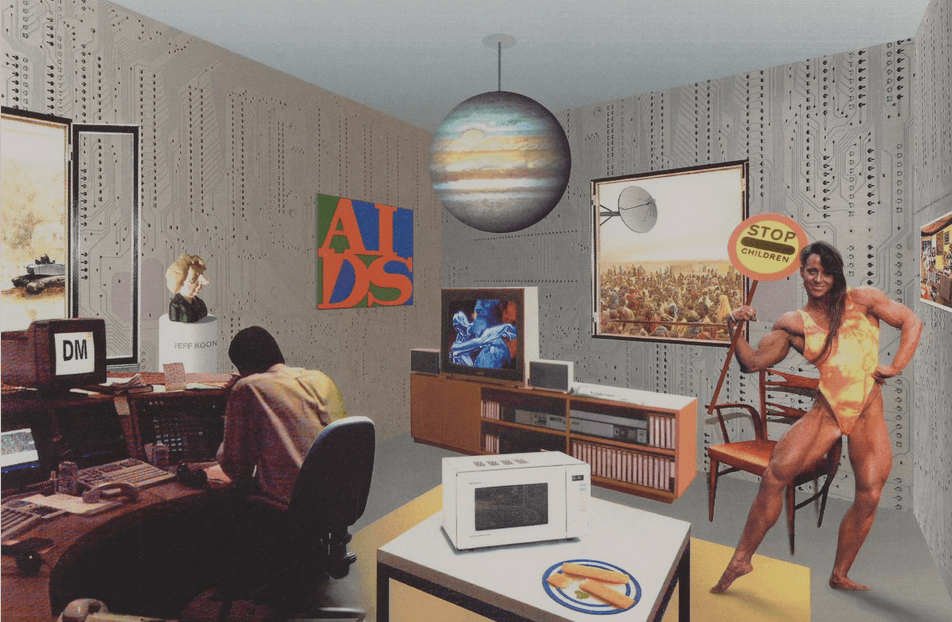

In 1956, for the landmark exhibition “This Is Tomorrow” at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, Hamilton created what would become an icon: Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?. This 26 cm × 24.8 cm collage uses cut‑outs from American magazines: a bodybuilder father, a lampshade‑topped nude mother, a Stromberg‑Carlson television, and even a Tootsie Pop with the word “POP” emblazoned on its stick.

Styled like a consumer‑magazine headline, the title itself is a clever critique of post‑war materialism . Hamilton Richard Hamilton was a pioneering figure in the domain of Pop Art, contributing significantly to the development and international recognition of this artistic movement. His profound impact on shaping the identity of Pop Art extends beyond geographical borders, making him a crucial figure in the realm of international art. later defined Pop Art as: “popular, transient, expendable, low‑cost, mass‑produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business” —effectively naming and shaping the movement’s identity.

This seminal piece, now housed at Kunsthalle Tübingen, Germany, served as a visual manifesto: a domestic “Adam and Eve” surrounded by the temptations and hyper‑consumerist aesthetics of the era.

Hamilton’s Political Imagery and Media Commentary

Unlike many Pop artists who focused solely on style, Hamilton engaged with political issues and media imagery throughout his career. His Swingeing London series (1967–69) depicted Mick Jagger and dealer Robert Fraser handcuffed after a drug raid—a daring commentary on celebrity and justice.

The 1981‑83 series The Citizen portrays IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands as Christ, a pointed critique on martyrdom and media spectacle. In the mid‑2000s, Shock and Awe skewered Tony Blair’s Iraq War policies by depicting him as a cowboy, double‑holstered for combat .

Hamilton believed in the power of imagery to shape perception. In his 1959 lecture “Persuading Image”, he observed how consumer culture manipulates desire. His art continuously probes this theme, reflecting on the “look of things” he forecast as essential to modern life.

Legacy: Teaching, Duchamp, and Global Influence of Hamilton

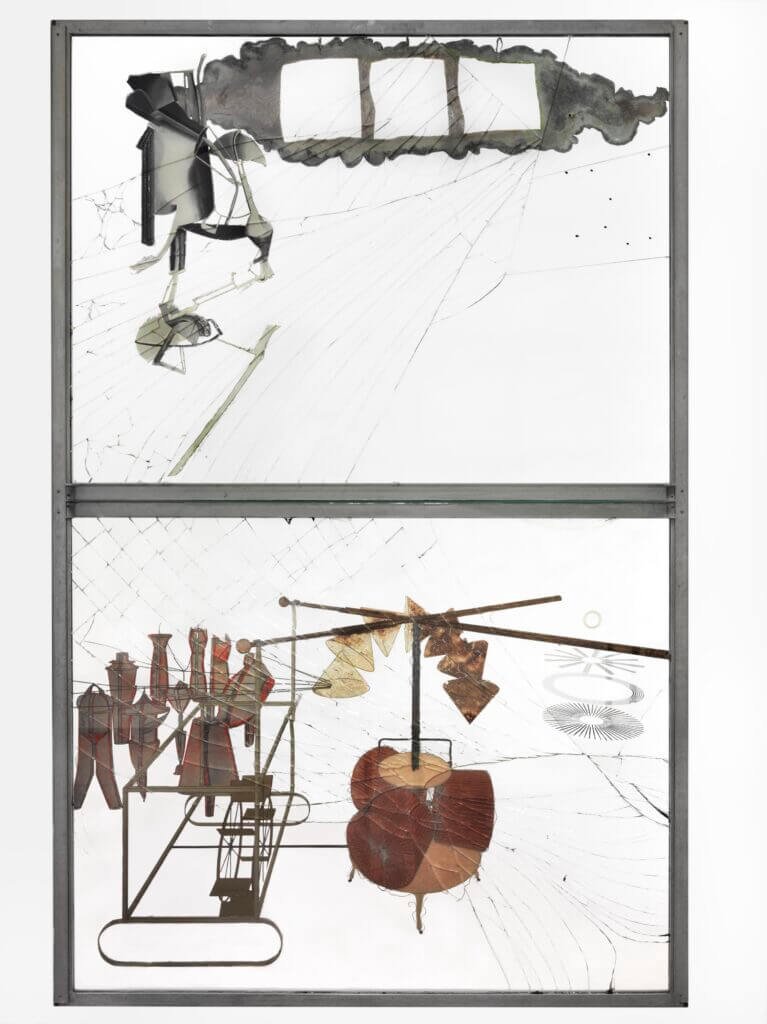

From the late 1950s through the 1960s, Hamilton taught at the Royal College of Art and Newcastle—mentoring luminaries like David Hockney, Peter Blake, and Bryan Ferry . He also curated the first major British retrospective of Marcel Duchamp at Tate in 1966, published Duchamp’s Green Box notes in 1960, and reconstructed The Large Glass (1915–1923) in 1965–1985.

Hamilton’s diverse talents earned him retrospectives at institutions like the Tate (1970, 1992), Solomon R. Guggenheim (1973), MACBA (2003), and Tate Modern (2014). His influence reached far beyond Britain—shaping American media art and leaving a lasting imprint on Asian art markets, including in Singapore.

Richard Hamilton Pop Art’s Influence and Legacy

Richard Hamilton’s influence on the art world is both foundational and far-reaching. As one of the first artists to integrate popular culture, advertising, and mass media into fine art, he redefined what could be considered “art” in the postwar era. His 1956 collage Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? didn’t just spark the Pop Art movement—it challenged centuries-old hierarchies between high art and commercial imagery.

Hamilton’s work laid the conceptual and visual groundwork for generations of artists who followed. From Andy Warhol’s screen-printed celebrity portraits to Damien Hirst’s provocative installations, echoes of Hamilton’s thinking can be seen across decades and continents. His approach, which embraced irony, consumer critique, and visual experimentation, opened the doors for multimedia practices that now dominate contemporary art.

Beyond style, Hamilton had a deep impact on the intellectual structure of art-making. His engagement with Marcel Duchamp and his teaching role at institutions like the Royal College of Art helped reintroduce conceptual rigor into visual culture. He taught artists not just how to make images, but how to think about them—how to question, decode, and recontextualize.

From Europe to North America and increasingly in Asia, Hamilton’s legacy continues to shape how art interacts with society. In a world where media saturation and consumerism define daily life, his ability to turn everyday culture into critical visual language feels more relevant than ever. Hamilton didn’t just comment on the art world—he rewired it.

Why Hamilton’s Pop Art Still Matters Today

-

Pop Art Pioneer: His early collage redefined art by foregrounding everyday objects and mass media as subjects worthy of critique and celebration.

-

Cultural Critic: Through political work, Hamilton showed that Pop imagery can also be deeply subversive.

-

Cross‑disciplinary Experimenter: He blurred the lines between fine art, design, publishing, and technology—trends now central in global art ecosystems.

-

Global Reach: From America to Singapore, his work remains a reference for analyzing consumer culture and visual saturation.

-

Thoughtful Educator: As a teacher and curator, Hamilton shaped future generations of artists and played a pivotal role in preserving key avant‑garde legacies.

Conclusion: A Visionary Ahead of His Time

Richard Hamilton was not merely a stylistic innovator—he was a conceptual visionary who understood that images shape society and that art must interrogate its own tools. From the domestic satire of Just What Is It… to the political resonance of The Citizen, and the digital layers of his late work, Hamilton’s oeuvre remains rich, provocative, and relevant.

His legacy is especially poignant in contexts like international art scene that continue to grapple with globalization, media influence, and cultural identity. As museums, galleries, and artists in those regions engage with mass imagery, Hamilton’s ideas resonate powerfully: art must not only reflect the world—but ask “Just what is it…?” and demand an answer.

[/ux_text]