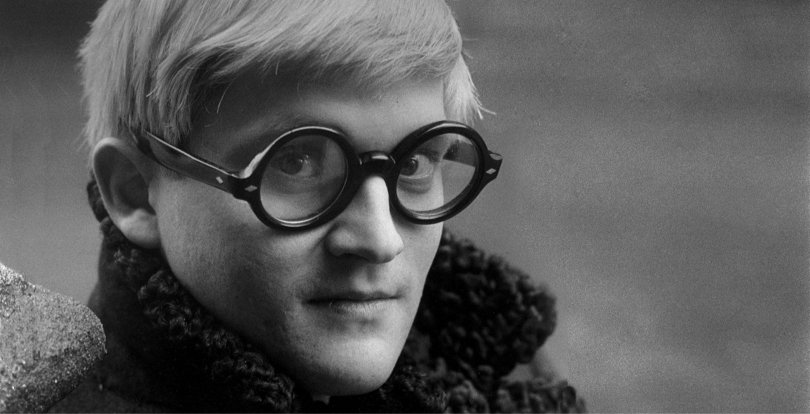

Who Is Eduardo Paolozz?

Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005) was one of the most radical and visionary artists of the 20th century, whose work bridged Surrealism, Pop Art, and Brutalism. He was also a founding member of the Independent Group, a collective of artists and thinkers who challenged conventional boundaries between high and low culture. As a pioneering sculptor, printmaker, and collage artist, Paolozzi’s creative language was rooted in experimentation. He dissected modern life using collage and assemblage, wielding the debris of the industrial age—scrap metal, mass media clippings, and cultural leftovers—not as trash, but as raw material for building meaning. Across his vast body of work, Paolozzi approached the chaos of the contemporary world not with nostalgia, but with an unsparing curiosity that questioned consumerism, psychology, and the machine age.

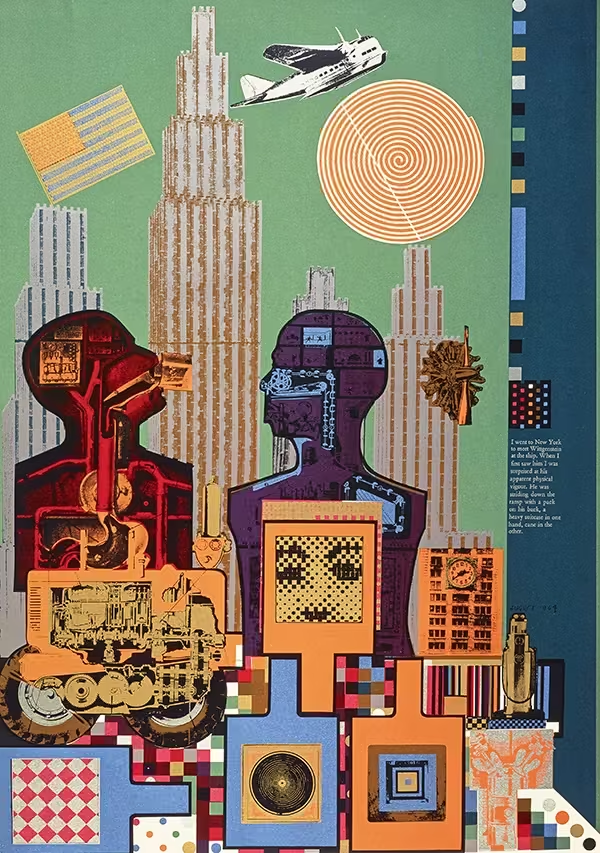

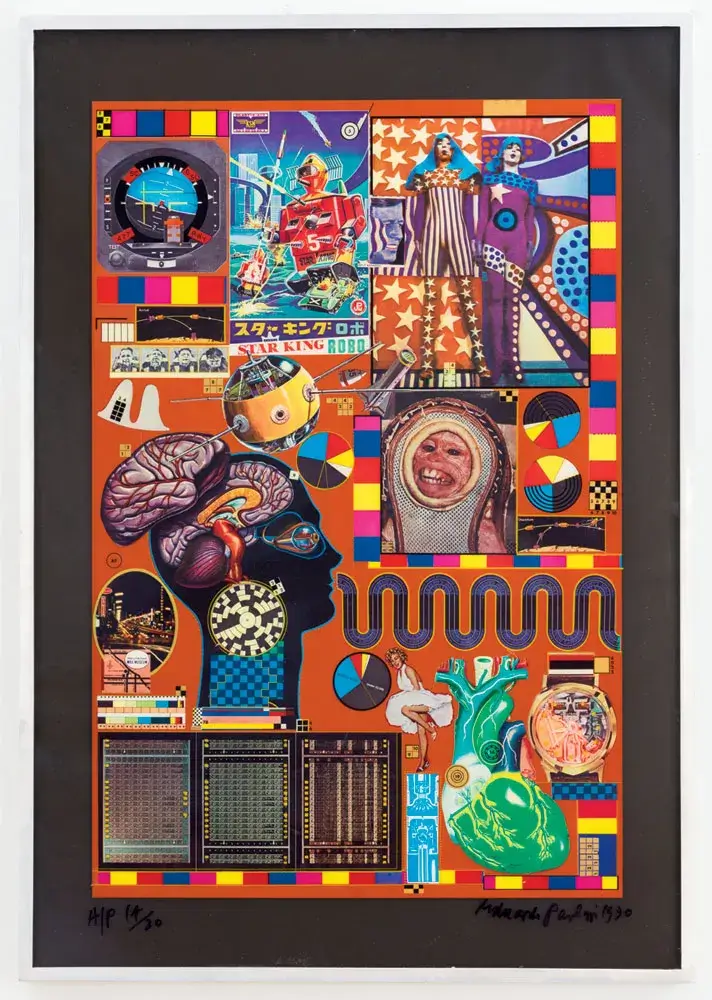

At the heart of Paolozzi’s art lies a bold embrace of fragmentation, appropriation, and transformation. He treated the cultural overload of the postwar world—its advertisements, television, mechanical devices, and psychological theories—as a puzzle to reconfigure. His work wasn’t about resolving disorder but revealing how meaning is made from fragments. Paolozzi used collage and sculpture to capture the anxiety, humor, and contradictions of modern life, giving form to the subconscious experience of being human in a rapidly industrializing and commercialized society.

Paolozzi’s New Visual Language from the Rubble of Modernity

Emerging from the trauma of World War II, Paolozzi’s early career was marked by the search for a new visual language that could speak to the dislocation and absurdity of the time. Traditional forms of painting or sculpture no longer seemed sufficient. Instead, he turned to what surrounded him—advertisements, comic strips, toy catalogues, anatomical drawings, technical manuals. These everyday images, consumed and discarded, became the grammar of his visual communication.

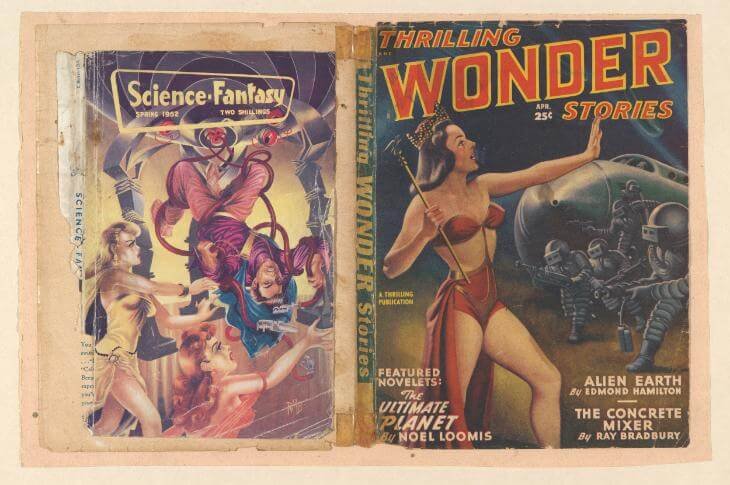

Paolozzi’s groundbreaking collage I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947) stands as a seminal work in the genesis of Pop Art. By juxtaposing imagery such as a pin-up model, a Coca-Cola logo, and a military aircraft—all sourced from American mass media—he created a chaotic yet deliberate tableau. More than a stylistic innovation, this work served as a sharp critique of how consumer imagery and wartime propaganda shaped public perception and personal identity. It exemplified his signature strategy of using cultural fragments to expose psychological and societal disintegration in the postwar era.

Through his collages, Paolozzi created densely layered, multi-referential compositions that forced viewers to decode them. They served as cultural x-rays, exposing the layers of ideology beneath what appears mundane or entertaining. For Paolozzi, mass media wasn’t passive material; it was both the symptom and source of modern anxiety.

Appropriation as Artistic Method and Social Commentary

Paolozzi’s artistic method was deeply rooted in appropriation—taking existing images, objects, and ideas and recontextualizing them to reveal hidden meanings. His series Bunk! (1952), a slide presentation of collages created from American pulp magazines, was a direct commentary on the rise of American popular culture and its influence over British society. In doing so, Paolozzi anticipated the strategies that would later define Pop Art.

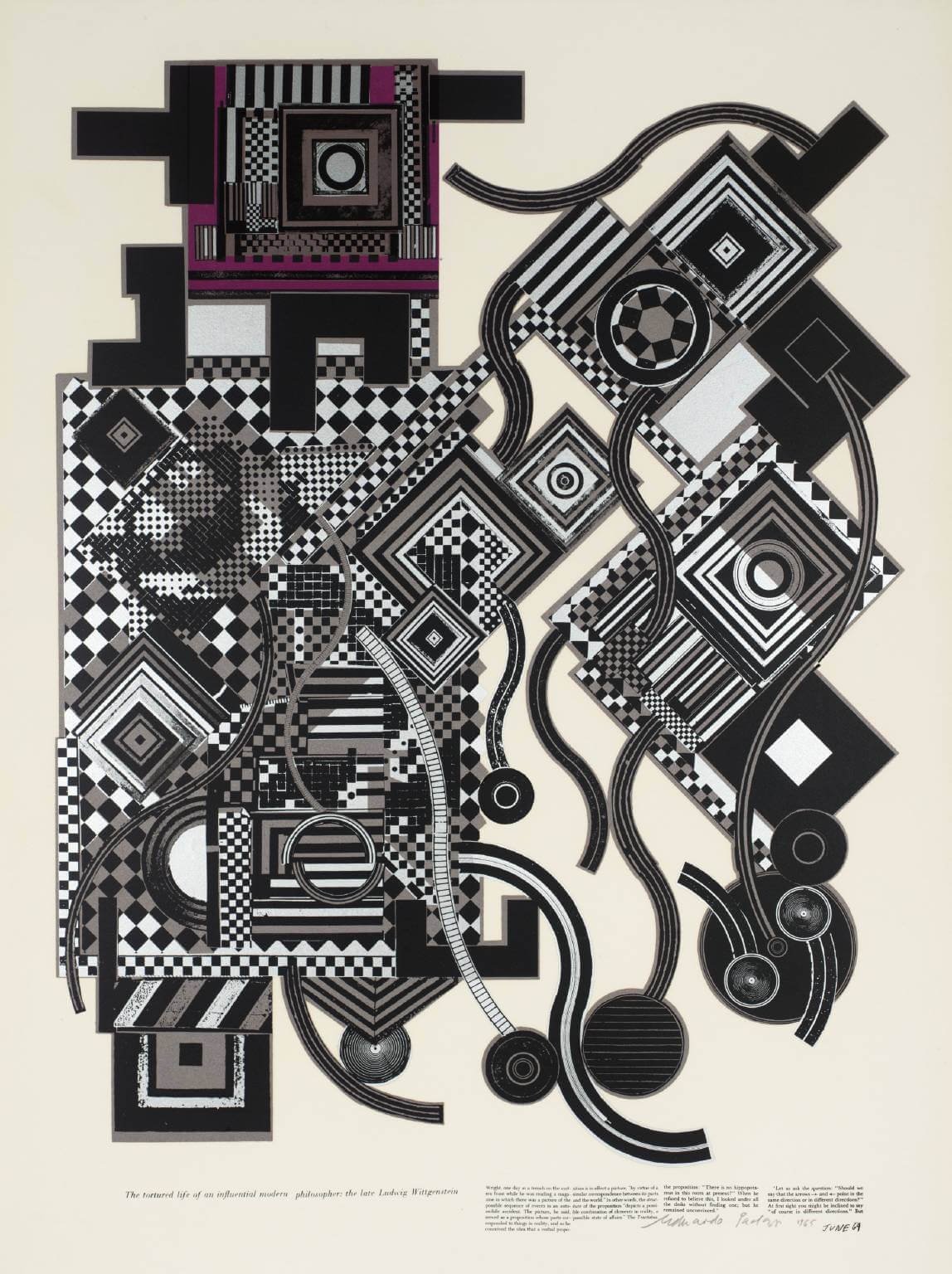

But unlike Warhol’s cool repetition or Lichtenstein’s ironic detachment, Paolozzi’s approach was far more analytical and psychological. He wasn’t celebrating consumer culture so much as dissecting it. By appropriating advertisements and pseudo-scientific diagrams, he pointed to the constructed nature of identity, desire, and power in the modern world.

This appropriation extended beyond two dimensions. In sculpture, he salvaged machine parts, wires, springs, and broken tools to create human-like figures—cyborgs before the term entered pop consciousness. His bronze sculpture Man Machine (1950s) presents a mechanical body that is neither fully human nor fully robotic. This hybrid form expressed the loss of spiritual wholeness in a world increasingly defined by mechanization.

Junk Transformed: Paolozzi’s Visionary Use of Waste

One of Paolozzi’s most radical gestures was his use of junk and discarded materials. Far from romanticizing them, he treated waste as the foundation for artistic and cultural transformation. In this, he aligned with the ethos of Brutalism, which celebrated raw materials and exposed structures.

His sculptural practice involved assembling gears, engine parts, and scrap metal into expressive forms. These weren’t smooth or polished like classical sculpture; they were raw, heavy, and scarred—visual metaphors for the fractured condition of modern life. Paolozzi believed that in this detritus lay new possibilities for form and meaning.

“Metamorphosis Rubbish” a phrase often associated with his process, captures his paradoxical view: that from the overlooked and the ugly, something transformative could emerge. In doing so, he challenged the elitist standards of beauty in art. His work insisted that the discarded and the banal were not beneath art—they were essential to it.

Eduardo Paolozzi’s Collage and Assemblage as Psychological Exploration

Paolozzi’s fascination with the subconscious was fueled by both Surrealism and the postwar explosion of psychological theory. He frequently referred to his works as a kind of “Psychological Atlas”, borrowing the title from a 1930s psychology book—but reimagining it entirely. Rather than presenting objective maps of the human mind, Paolozzi’s works offered kaleidoscopic visions of internal conflict, cultural programming, and dream logic.

His method mirrored the processes of memory and thought—nonlinear, associative, layered. In sculpture, he brought this sensibility into three dimensions. Works such as The Whitworth Tapestry and The Lost Magic Kingdoms series revealed his ongoing interest in cognitive mapping, mythology, and anthropology.

Assemblage became a way to externalize mental states. The forms often appear half-built or decaying, suggesting the instability of identity and the mind. This was not nihilism, but a kind of realism—a reflection of how the self is shaped by media, history, and machinery.

Machines, Men, and the Posthuman Condition in Paolozzi’s Art

A defining obsession in Paolozzi’s art is the machine—not just as a physical object, but as a metaphor for the modern condition. He did not merely represent machines; he absorbed their logic into his artmaking. The mechanized aesthetic of his sculptures reflects a world where human beings are increasingly inseparable from technology.

Yet Paolozzi’s machines are never simply cold or clinical. They evoke pathos, humor, and even tenderness. His cyborgs and robot-like figures often appear vulnerable, caught between organic life and industrial form. They embody the anxieties of a society on the threshold of automation, artificial intelligence, and mass surveillance.

In today’s context, Paolozzi’s work can be read as a prescient meditation on the posthuman condition. He anticipated the fusion of man and machine, and the psychological consequences of living within technological systems that exceed individual control.

Legacy and Relevance of Paolozz

Eduardo Paolozzi’s legacy is vast and enduring. His experimental use of collage, found materials, and mass media has influenced generations of contemporary artists—from installation art and conceptualism to digital remix culture. His works challenge the viewer not just to look, but to think—about how images, objects, and systems shape our understanding of self and society.

In a world saturated with visual information, Paolozzi’s approach remains strikingly relevant. He reminds us that art can be both chaotic and deeply coherent, that the fragments of culture carry truths waiting to be reassembled. Whether we call him a Pop Artist, a Surrealist engineer, or a modern myth-maker, Paolozzi’s vision offers a radical blueprint for how to make sense of a fragmented world.

Final Thoughts

Eduardo Paolozzi was more than an artist; he was a philosopher of images, a sculptor of ideas, and a prophet of technological modernity. Through fragmentation, appropriation, and transformation, he forged a visual language that captured the contradictions of the 20th century and anticipated the complexities of the 21st. In turning the debris of consumer culture into works of lasting power, Paolozzi didn’t just comment on the world—he rebuilt it.