Sculpting the Unspoken: Trauma and the Birth of Art

Bourgeois’s recurring themes—abandonment, revenge, vulnerability—root deeply in her experience of birth as trauma. She described being born as being “ejected and abandoned,” a primal wound that haunted her art. This experience of being cast out of intrauterine security becomes a recurring metaphor in her works. Unlike traditional representations that attempt to re-present trauma, Bourgeois’s art is more aligned with figuring it, using form to bring forth sensations that were never captured in language to begin with.

In Schiller’s reading, Bourgeois’s practice aligns with what psychoanalysts César and Sara Botella term regredience—a creative process akin to dreaming that reaches into preverbal, ahistorical affect and expresses it through form. Her sculptures become psychic gestures that build new connections to previously unrepresented zones of feeling.

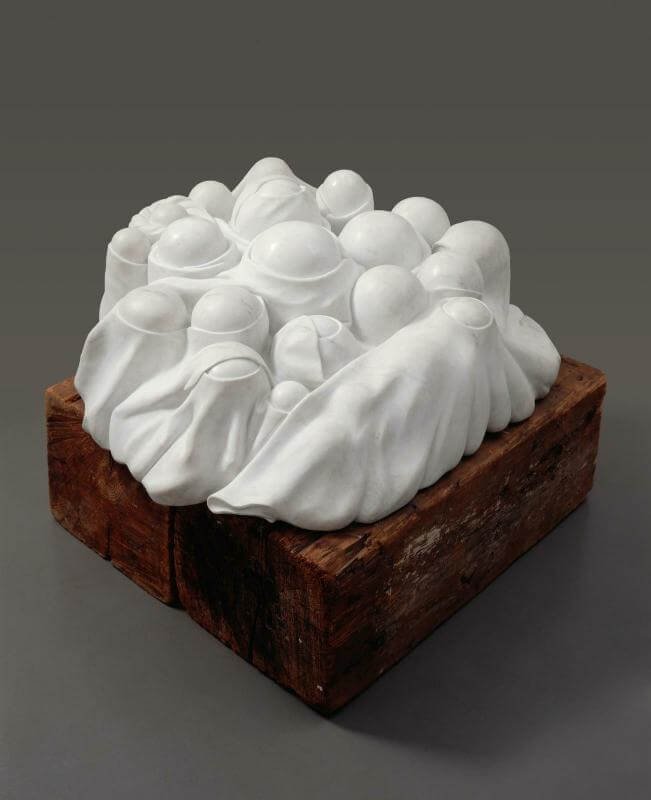

Fée couturière: The Nest as Womb and Psyche

In Fée couturière, Bourgeois creates a hollow, nest-like form—a suspended plaster structure pierced with holes and openings. It invites the viewer to reach inside, to engage through touch rather than sight. The piece becomes an analog to intrauterine space, a cocoon of psychic gestation. Its name, referencing the tailorbird, evokes her mother and the act of stitching—a nod to both domestic craft and emotional repair.

The nest functions as a metaphor for the protective maternal body and for the inner recesses of the psyche. As Schiller notes, it is not simply a sculpture, but an emotional environment that holds within it the echoes of early life and preverbal distress. Its tactile engagement asks the viewer to experience the sculpture not through analysis but through bodily intuition.

Le Regard (1966): The Gaze and the Threshold of Birth

Le Regard (1966) presents a latex sculpture resembling a vaginal opening that simultaneously suggests an eye—an orifice of both emergence and observation. The piece is unsettling in its ambiguity: both soft and fleshy, yet haunting and resistant. For Bourgeois, the slit does not invite entrance; rather, it hovers at the boundary of inside and outside, self and other, trauma and emergence.

Here, birth becomes spectacle, and the gaze—often male and intrusive—is reversed. The vaginal becomes ocular. The observer is observed. Bourgeois turns the traditional dynamics of voyeurism inward, reframing female genitalia not as passive subject but as active viewer, capable of holding power and memory. The sculpture reveals Bourgeois’s capacity to subvert psychoanalytic tropes through her unique visual grammar.

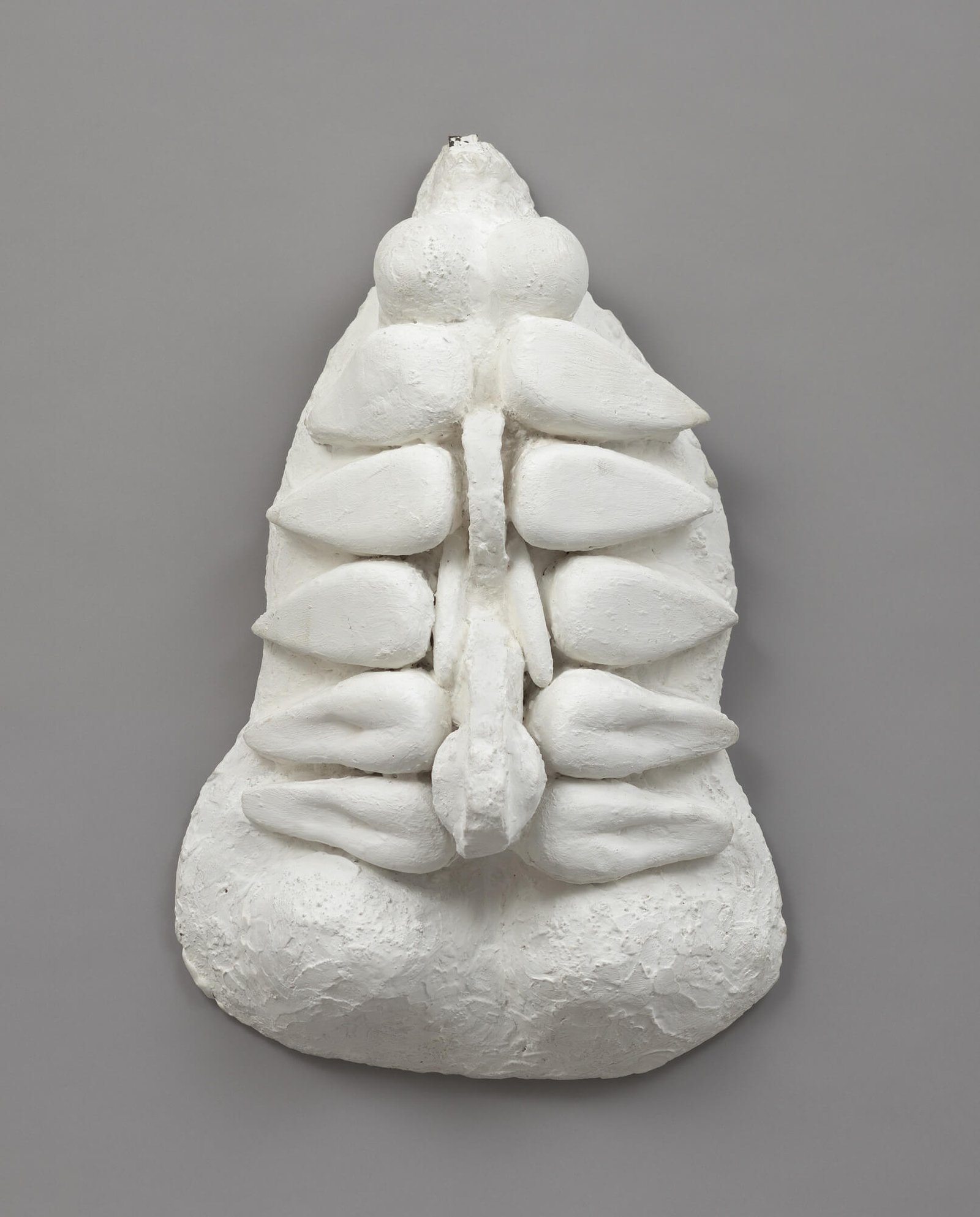

Portrait (1963): Matter Before the Mind

In Portrait (1963), Bourgeois offers a wall-mounted latex relief that defies figurative logic. With its mottled surface and amorphous forms, it presents a chaotic pre-subjective state. Schiller compares it to what the psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion called O—the unknowable, ungraspable core of reality. It’s not a representation of a person, but of the self before identity, before ego, before narrative.

This is figurability at its most abstract—the presentation of what cannot be pictured, only felt. It is not a self-portrait but a portrait of loss of self, of fragmentation, of the desire to return to a prenatal unity. Schiller argues that Bourgeois’s choice of materials—latex, often poured or shaped by gravity—aligns with her aim to let the unconscious form itself without control or design.

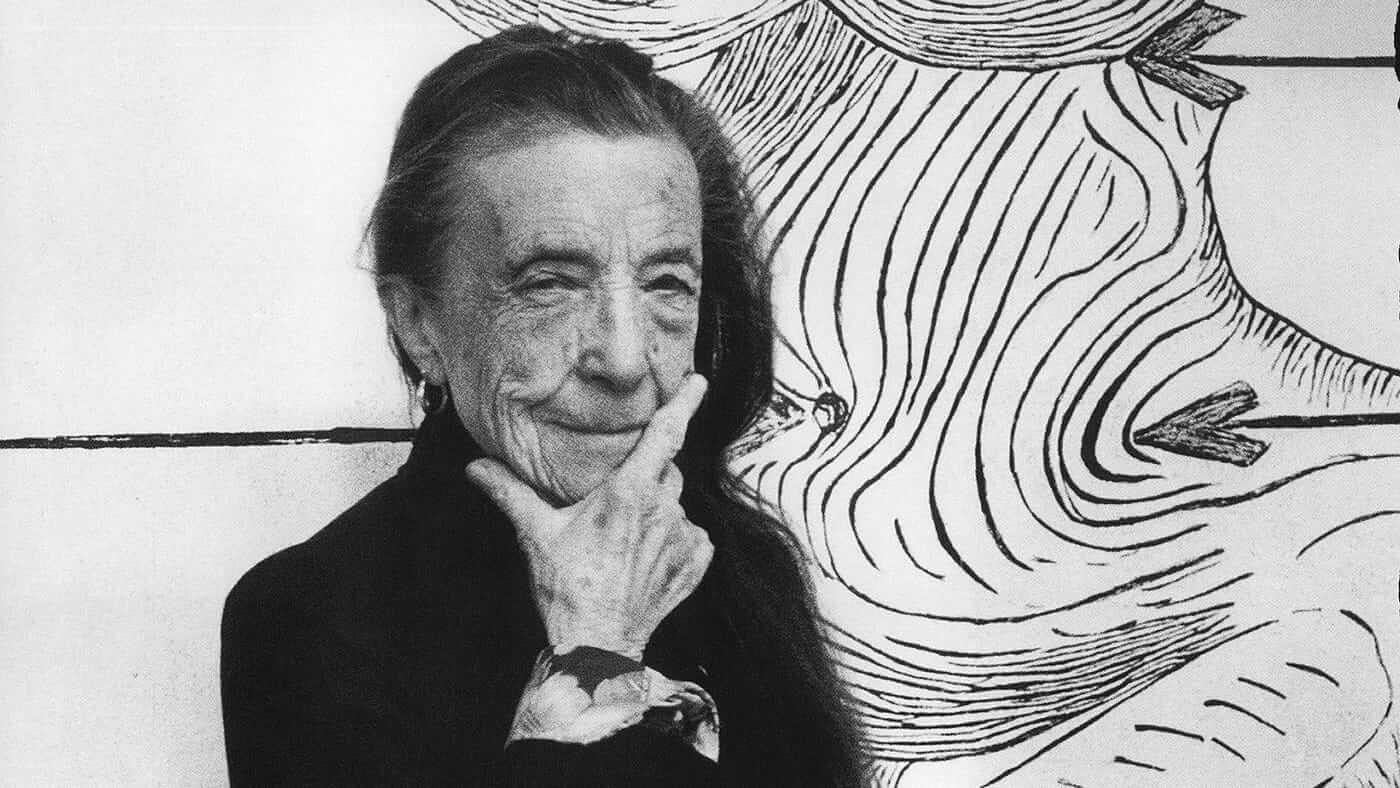

Louise Bourgeois: Emotional Threads in Art

Schiller aligns Bourgeois’s practice with the Botellas’ concept of regredience, distinguishing it from regression. While regression implies psychic retreat, regredience is a productive state of psychic reverie, enabling the transformation of unrepresented affect into form. Bourgeois’s creative process mirrors the dream-work that Freud theorized: not reconstructing memory, but creating something new from the remains of the unconscious.

Bourgeois becomes not just an artist but a weaver of psychic threads. Her sculptures stitch together fragments of memory, bodily sensation, and fantasy. Each work becomes a psychic container—a womb of meaning—where unspeakable trauma can be safely held, shaped, and shown.

From the Unconscious to the Gallery: Bourgeois’s Psychoanalytic Legacy

Bourgeois’s work challenges the distinction between personal and universal trauma, inviting viewers to confront their own affective landscapes. Her practice of giving form to the formless anticipates themes in feminist theory, particularly Luce Irigaray’s writings on mucous, vaginal textures, and pre-linguistic sensation.

Her legacy is not only aesthetic but deeply therapeutic. As she once said, “The work is finished when the anxiety disappears.” Her sculptures are dreams made solid, nightmares you can touch. They resist traditional interpretation, inviting instead an erotics of form—a surrender to feeling.

Conclusion: The Shape of What Haunts Us

Through figuration, Louise Bourgeois built a visual language for fear, abandonment, and birth trauma—a language forged not in words, but in flesh, fiber, and latex. Her work does not just illustrate emotion—it embodies the process of surviving it. By making the invisible visible, Bourgeois transforms private pain into shared psychic experience.