Discover how personal tragedy shaped René Magritte’s surrealist masterpieces. Explore the hidden meanings behind his iconic artworks and the psychological impact of trauma on his vision.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Early Life and Tragic Events

Being born on November 21, 1898, in Lessines, Belgium, Rene Magritte’s childhood was relatively unremarkable until the tragic death of his mother, Régina, in 1912. Régina’s suicide by drowning in the Sambre River left a lasting emotional scar on Magritte. The circumstances surrounding her death, including the discovery of her body with her nightgown covering her face, haunted Magritte throughout his life and deeply influenced his art.

René Magritte’s artistic style is a captivating blend of precision, surrealism, and philosophical inquiry. Known for his meticulous attention to detail and imaginative compositions, Magritte explores the boundaries between reality and illusion with thought-provoking symbolism and dreamlike imagery. His paintings invite viewers into a world where familiar objects are imbued with new meanings, challenging perceptions and prompting deeper contemplation of the human condition and the nature of existence itself. Magritte’s unique approach continues to fascinate and inspire audiences, making him a seminal figure in the realm of modern art.

Psychological Themes in Magritte’s Art

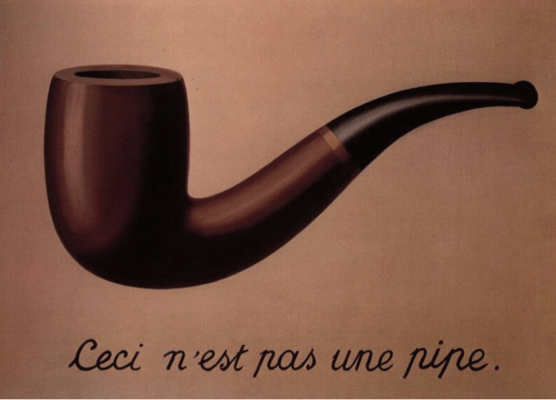

One of the most prominent psychological themes in Magritte’s work is the tension between appearance and reality. His paintings often feature ordinary objects placed in unusual contexts or depicted in ways that disrupt our expectations. This visual trickery highlights the limitations of human perception and challenges the viewer’s understanding of the world. For example, in his famous painting The Treachery of Images (1928-1929), Magritte depicts a pipe with the inscription “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (This is not a pipe). The image of the pipe, though realistic, is a representation of a pipe, not the object itself. This simple yet profound statement forces the viewer to confront the difference between an object and the way it is perceived or symbolized. The painting underscores the idea that our perception of reality is always mediated by representation, and that the mind is often tricked by appearance.

The Treachery of Images by Rene Magritte (1929).

The Treachery of Images by Rene Magritte (1929).

Impact of Trauma on Magritte’s Artistic Expression

The trauma of losing his mother at a young age likely contributed to Magritte’s fascination with themes of concealment, hidden identities, and the mysteries of the human psyche. His art became a way to explore and confront his emotions in a symbolic and metaphorical manner. By transforming personal trauma into universal themes, Magritte created artworks that resonate deeply with viewers, inviting them to contemplate the complexities of human experience.

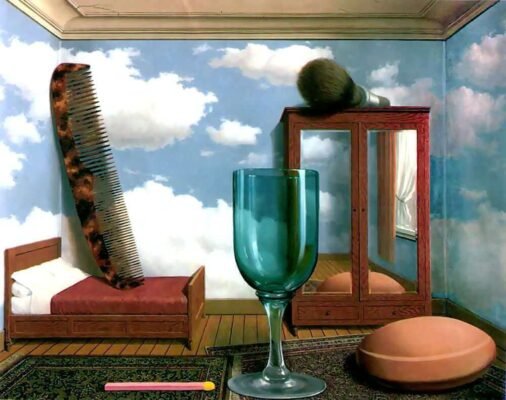

Personal Values by Rene Magritte (1952).

Personal Values by Rene Magritte (1952).

Magritte and Surrealism: Reflecting Sexual Fantasy and Expressing Sexual Inhibition and Frustration

Surrealism, as a movement, sought to explore the subconscious mind and challenge societal norms through unconventional and dreamlike imagery. For René Magritte, surrealism provided a platform to express both sexual fantasy and the repression and frustration associated with sexual inhibition.

Surrealism as a Psychological Playground

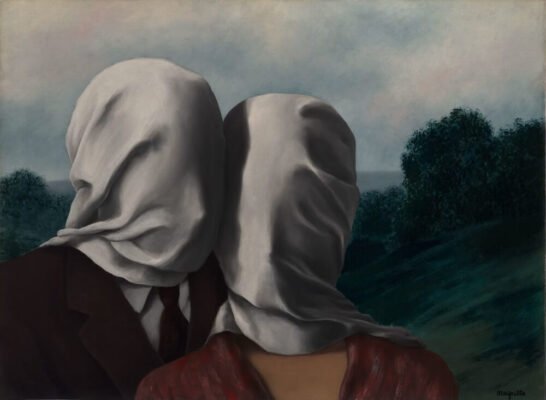

Another recurring theme in Magritte’s work is the notion of concealment—both in the literal sense of objects being hidden and in the psychological sense of repressed desires or fears. Many of Magritte’s works feature figures or faces partially obscured, creating a sense of mystery and inviting the viewer to question what is hidden from view. In paintings like The Lovers (1928), where a couple is shown kissing with cloth covering their faces, Magritte evokes the idea of emotional or psychological barriers. The obscured faces suggest that intimacy is not always fully accessible or truthful, and that there are aspects of the self and others that remain concealed or repressed. This theme of concealment could reflect Magritte’s own experience with emotional trauma, particularly the suicide of his mother when he was a teenager. The act of repression—pushing uncomfortable feelings into the unconscious—becomes a central motif in his work, representing the way the mind deals with pain and loss.

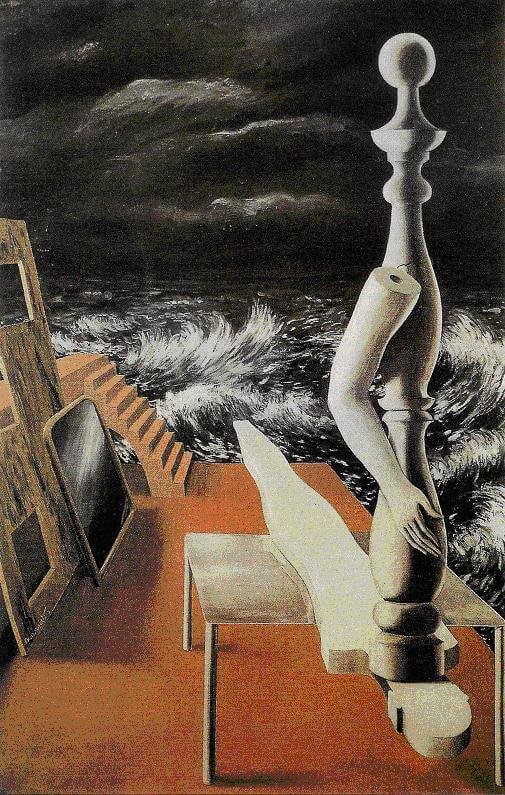

The Birth Of Idol by Rene Magritte (1926).

The Birth Of Idol by Rene Magritte (1926).

Eros, Violence, and Eroticism in Magritte’s Art.

Magritte’s work also reflects a more ambiguous, sometimes violent, relationship between the erotic and the repressed. His use of erotic symbols, such as the bowler-hatted men who frequently appear in his paintings, can carry connotations of masculinity and desire. However, these figures are often placed in strange, unsettling contexts that displace the erotic from its traditional associations with beauty or intimacy.

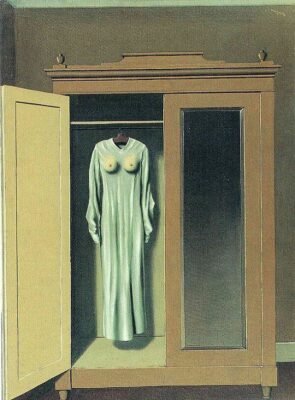

In Homage to Mack Sennett (1934), a provocative title that directly engages with sexual themes, Magritte combines eroticism with intellectualism. In many of his works, sexuality is presented as a form of power or control, as in The Garden of Delights (1954), where an erotic scene is transformed into a sterile and surreal image that questions the idea of sexual pleasure and desire. These works suggest that sexuality, far from being a liberating force, is also bound up in social conventions, repression, and the limits of human experience.

Homage to Mack Sennett by Rene Magritte (1934).

Homage to Mack Sennett by Rene Magritte (1934).

Phallic and Feminine Symbols

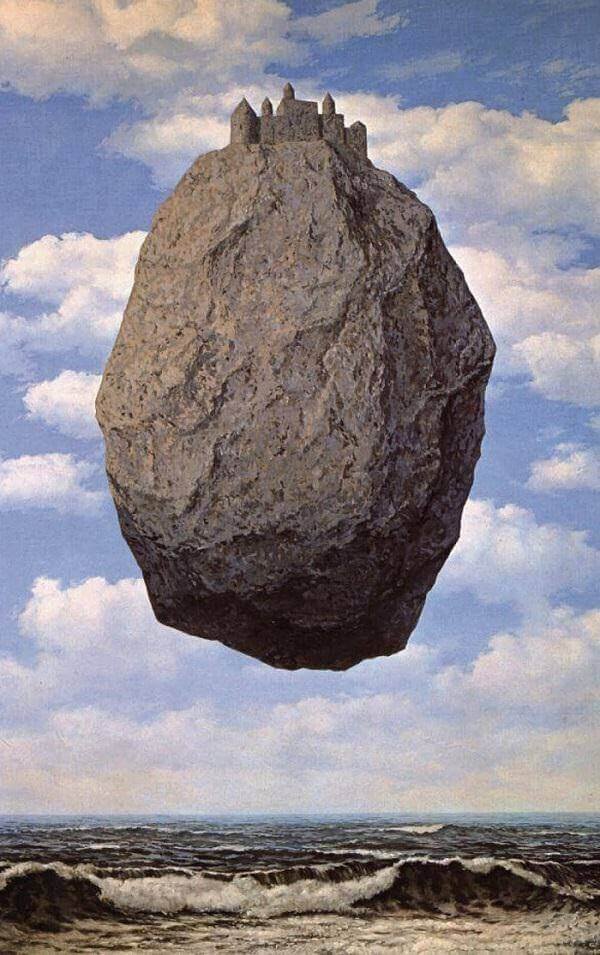

Magritte’s symbolism often evokes phallic and feminine imagery, though these symbols are never overt or explicit in a conventional sense. For example, in The Castle in the Pyrenees (1959), a massive, disembodied male figure stands atop a floating rock, its genitalia visible in a way that could be seen as a subtle phallic symbol. The floating castle and rock suggest a disconnect between the physical body and the unconscious, while the disembodied male figure hints at the symbolic castration of sexual identity.

The Castle in the Pyrenees by Rene Magritte (1959).

The Castle in the Pyrenees by Rene Magritte (1959).

Similarly, in The Lovers I (1928), a reclining figure appears to be interacting with an elongated object or appendage, which could be interpreted as a subtle reference to sexual penetration or desire. This ambiguous imagery suggests the tension between the individual’s sexual desires and the ways in which those desires are repressed or sublimated by society.

The Lovers I by Rene Magritte (1928).

The Lovers I by Rene Magritte (1928).

Critique of Sexual Repression

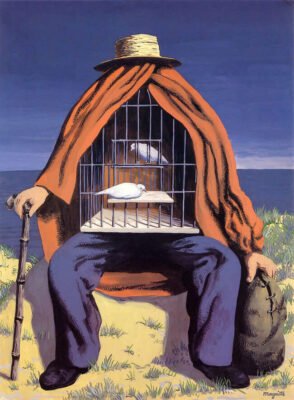

In works like The Key to Dreams (1930) and The Therapist (1937), Magritte critiques the societal norms that restrict sexual expression and inhibit individual freedom. Through surrealism, he sought to dismantle the barriers that separate the conscious from the unconscious, revealing the hidden desires and anxieties that shape human identity.

The Therapist by Rene Magritte (1937).

The Therapist by Rene Magritte (1937).

Escaping Rational Thought: Rebellion Against the Ordinary

In much of Magritte’s work, the act of “escaping” the confines of ordinary experience is achieved by placing everyday objects in unfamiliar, surreal contexts. This interplay of the familiar and the unfamiliar forces the viewer to question their perceptions of reality. Magritte often took ordinary objects—like a floating apple, a cloud-filled sky, or a bowler-hatted figure—and presented them in ways that defied their conventional meanings.

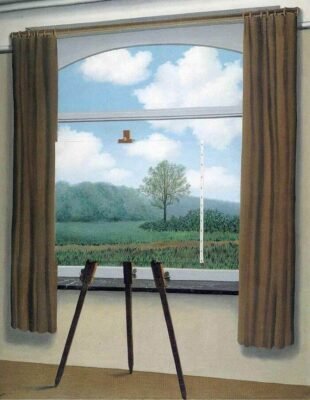

In The Human Condition (1933), for example, Magritte depicts a painting of a landscape positioned in front of a window, where the scene within the painting perfectly matches the view seen through the glass. This creates a visual paradox, making the viewer reconsider the relationship between the real world and its representation, and blurring the boundaries between perception and reality.This paradoxical statement challenges the viewer’s understanding of representation by highlighting the difference between the object and its image.

The Human Condition by Rene Magritte (1933).

The Human Condition by Rene Magritte (1933).

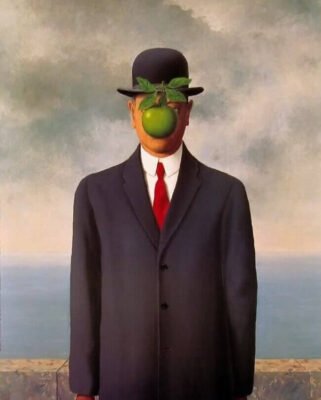

Escaping the Self: Exploration of Identity and Consciousness

For Magritte, surrealism also provided a means of escaping from the rigid, socially constructed notions of identity. His recurring use of self-portraits and representations of faceless figures suggests a deep engagement with questions of selfhood and the limits of personal identity. In works such as The Son of Man (1964), where a man’s face is hidden behind an apple, the obscured identity can be interpreted as a metaphor for the ways in which individuals hide their true selves—either from others or from their own understanding. The surreal, enigmatic nature of the painting invites viewers to question the nature of the self, to wonder whether it is something inherently visible or if it remains obscured, even to the individual.

The Son of Man by Rene Magritte (1964).

The Son of Man by Rene Magritte (1964).

Magritte’s exploration of identity can also be viewed in the context of his own life and the themes of repression and concealment that he grappled with after his mother’s death. In many ways, surrealism offered Magritte a language through which he could engage with the complexities of his own psychological landscape, allowing him to express feelings of alienation, fragmentation, and loss. His work became a form of escape, not into a fantastical or dreamlike realm, but into a space where he could reframe and reimagine his internal world.

Escaping the Constraints of Artistic Tradition

Beyond its psychological and personal implications, surrealism also served as a means for Magritte to break free from the constraints of traditional artistic styles. Before embracing surrealism, Magritte studied classical techniques and worked in commercial art. His early involvement in the artistic establishment, however, did not prevent him from seeking new ways to express himself. Surrealism allowed him to distance himself from the formalism and rationality that governed academic art, replacing it with an art that valued imagination, the subconscious, and the irrational.