“I try to apply colors like words that shape poems, like notes that shape music.” – Joan Miró –

Joan Miró’s Early Years and Influences in Barcelona (1893–1927)

Joan Miró was born on April 20, 1893, in Barcelona, Spain, to a family of artisans. From a young age, Miró showed an interest in drawing, and he pursued formal art training at the Escola de la Llotja in Barcelona. During his early years, Miró was influenced by the work of several Catalan modernists, including his exposure to Post-Impressionism and the emerging avant-garde movements in Europe. He was particularly drawn to the Symbolist and Fauvist movements, which were known for their vibrant colors and emotive subjects.

In the early 1920s, Miró’s work was still rooted in a form of realistic representation. His early paintings often depicted landscapes, still lifes, and portraits, though they were infused with an intuitive sense of abstraction. His early work was influenced by Post-Impressionism and his admiration for the works of artists such as Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne. In addition to this, Miró was exposed to the modernist trends of Cubism, which was developing rapidly in Barcelona. These influences prompted a shift in his approach, leading him toward a more abstract and experimental style.

It was during this time that Miró’s first major break occurred. He moved to Paris in 1920, where he met several key figures in the avant-garde scene, including the poet and critic André Breton, the sculptor Alexander Calder, and the artist Pablo Picasso. This period in Paris proved formative for Miró, as he was introduced to the Surrealist movement, which would have a profound influence on his work in the coming years. Miró’s early exploration of abstraction and his exposure to Cubism and Expressionism laid the groundwork for his subsequent immersion in Surrealism.

Surrealism and the Development of Miró’s Signature Style (1927–1937)

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Miró became deeply involved with the Surrealist movement, which was centered around exploring the unconscious mind, dreams, and the irrational. Led by André Breton, Surrealism sought to break down the barriers between reality and fantasy, and it championed spontaneity, chance, and subconscious expression. Miró’s association with Surrealism marked a critical shift in his artistic style, as he increasingly moved away from conventional representation and embraced pure abstraction.

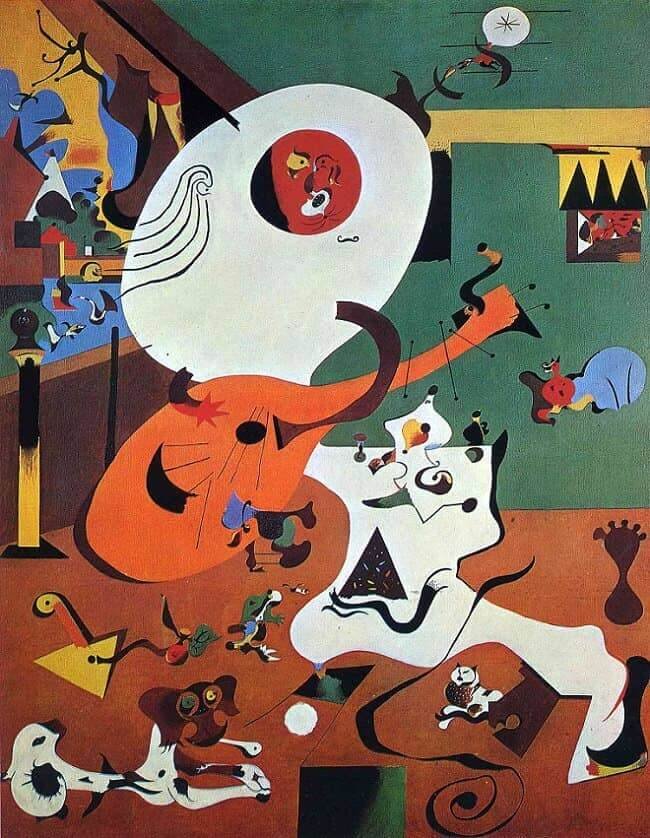

Miró’s engagement with Surrealism was partly inspired by his friendship with figures such as Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst, who were also part of the movement. During this time, he began to incorporate playful, organic forms and whimsical shapes into his paintings. His works were characterized by a sense of spontaneity, in which he sought to tap into the primal, subconscious energies of the mind. Miró’s paintings from this period frequently included biomorphic forms, otherworldly imagery, and imaginative creatures that appeared to materialize from a surreal, unconscious world. These works are often described as “automatic drawings” or “automatic paintings,” a technique where the artist would let their hand move freely across the canvas without conscious control, letting the subconscious mind guide the creation of the image.

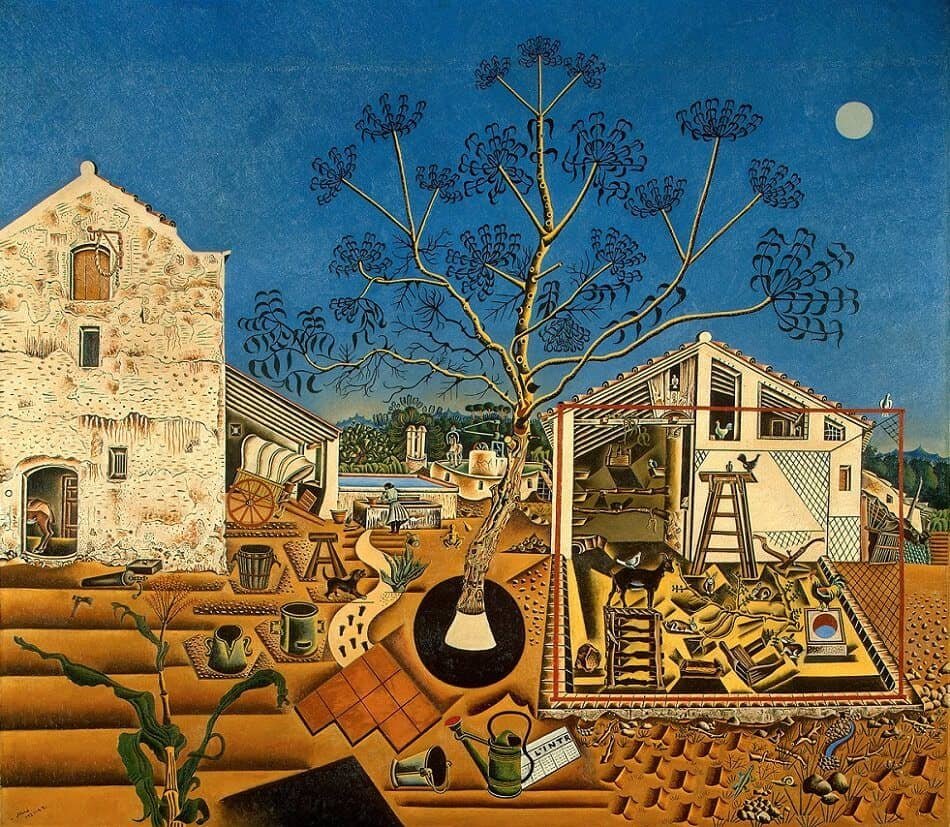

Some of Miró’s most famous works from this period include The Tilled Field (1923–1924), The Harlequin’s Carnival (1924), and Dutch Interior (1928). In these works, Miró’s exploration of the subconscious manifested in surreal, abstract depictions of human figures, animals, and landscapes. These paintings reflect the influence of his Surrealist contemporaries, especially in their focus on automatism and their avoidance of traditional perspective.

During the 1930s, as Europe grappled with the rise of fascism and political unrest, Miró’s art took on a more intense, expressive quality. Works such as The Farm (1922) demonstrates Miró’s increasing desire to confront the social and political climate of the time through his art. Miró was deeply affected by the rise of fascism in Spain and the Spanish Civil War, which began in 1936, and this period marked a shift toward more symbolic representations in his work. The fluid, playful imagery of earlier works gave way to darker, more aggressive forms, as Miró sought to convey the emotional and psychological tensions of the period.

The Influence of the Spanish Civil War and Political Activism on Joan Miró’s Art (1937–1940s)

The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 had a significant impact on Miró’s work. While he did not actively engage in the war as a participant, he became increasingly politically aware, and his work began to reflect the emotional toll of the conflict. Miró’s art during this period is often seen as a form of protest against fascism and the violent political upheaval in Spain. His style, while still deeply influenced by Surrealism, became more focused on abstraction and symbolism as a means of confronting the war’s devastating effects.

One of the key works from this period is The Reaper (1937), which is a powerful, symbolic image of death and destruction. The painting depicts a large, abstract figure, its aggressive, sharp forms evoking the violent imagery of war. Another notable work is Spanish Dancer (1939), which reflects Miró’s attempt to convey the emotional strain and psychological trauma caused by the war. These works, with their rough lines and dramatic color contrasts, exemplify Miró’s engagement with the political crisis of the time.

Miró’s political activism also extended beyond his artwork. He made public statements in support of the Spanish Republic and its fight against Franco’s fascist forces, and he sought to raise awareness about the suffering of the Spanish people. His involvement in political causes and his intense emotional response to the war led to his eventual decision to leave Spain and settle in Paris.

Miró’s Art Post-War Period: Return to Abstraction and New Experimentations (1940s–1960s)

After the end of the Spanish Civil War and the victory of Franco’s forces in 1939, Miró moved to Paris, where he continued to experiment with new techniques and concepts in his work. The years following the war marked a period of introspection and redefinition for the artist. His earlier focus on Surrealism was gradually replaced by a return to abstraction, and his work became more focused on the formal elements of art—line, color, and shape.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Miró’s work evolved into a more geometrically abstract form. He became increasingly interested in the idea of “pure” abstraction and began to experiment with different media, including ceramics, sculpture, and mural painting. His use of vibrant colors, particularly red, blue, and yellow, became a hallmark of this period. In works like The Woman and the Bird in front of the Sun (1942) and Mural for the Barcelona Pavilion (1955), Miró’s imagery became simpler and more iconic, with recurring motifs such as stars, moons, and birds.

This period also saw Miró’s exploration of printmaking, where he created a series of lithographs and etchings that allowed him to continue his exploration of abstraction in new formats. He became increasingly interested in the expressive potential of these mediums, using the printing process to create textured, dynamic works that reflected his continued experimentation with form and color.

Mature Work: Final Years of Joan Miró (1960s–1983)

In the final decades of his career, Miró’s work evolved into a more sculptural and monumental form. He continued to experiment with different materials and forms, creating large-scale public art projects, including murals, sculptures, and installations. One of his most famous late works is the Miró Foundation (1975), a museum dedicated to his life and work in Barcelona. This period also saw Miró creating several iconic sculptures, such as The Moonbird (1966) and The Woman and the Bird (1967), which used his characteristic playful forms and bright colors in a three-dimensional context.

Miró’s later works retained a sense of playfulness and abstraction, but they also reflected a deepening sense of introspection and contemplation. His imagery became even more pared-down, with a focus on simple, evocative shapes and symbols that seemed to speak to the universal experience. Miró’s mature art was concerned less with the political and social issues of his earlier years and more with the pursuit of artistic freedom and expression.

The Legacy of Joan Miró

Miró’s legacy extends far beyond his time, not only through his works, but also through institutions like the Joan Miró Foundation in Barcelona, which preserves his vision for future generations. His art continues to inspire and provoke, inviting audiences to see the world through a lens of pure imagination and unbridled freedom. By constantly seeking new ways to express the complexities of human existence, Joan Miró left an indelible mark on the art world, proving that the boundaries of creativity are limitless.

In the end, Miró’s life and work remind us that art is not just an expression of the visible world, but a gateway to understanding the unseen forces of the subconscious, politics, and the shared human experience. His artistic periods, diverse and constantly evolving, reflect a dedication to the endless search for truth, beauty, and meaning through visual expression, ensuring his place as one of the most groundbreaking and impactful artists of the 20th century.