Discover the Independent Group—this in‑depth exploration of British post‑war art, architecture, contemporary art, pop art, critical theory, and mass culture highlights how the Independent Group reshaped modern aesthetics in Britain.

Who Is The Independent Group?

The Independent Group emerged in the winter of 1952–53 as a radical cadre of artists, architects, critics, and writers who met at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA). Their mission transcended traditional fine art. Rejecting the elitist boundaries of modernist art, the Independent Group pursued an “aesthetics of plenty” by embracing mass-produced imagery, collage, popular culture, consumerism, and emerging technology. These elements became the foundation of British Pop Art and would deeply influence global contemporary art, exhibitions, and architecture for decades.

The Independent Group Origins: Post‑War Optimism & the ICA Forums

In the aftermath of World War II, British society faced scarcity and austerity. Yet, by the 1950s, mass media, American culture, and visual consumerism offered new inspiration for artists and architects. The Independent Group embraced this cultural shift. Through their ICA forums, they examined science fiction, advertising, Hollywood films, and industrial design, reshaping the language of modern art.

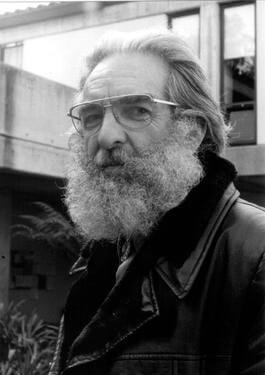

Eduardo Paolozzi, a founding member of the Independent Group, projected images from American magazines during the group’s early sessions. These meetings challenged the distinctions between “high art” and “low culture,” a theme central to contemporary art movements today.

Collage & “Found Object” Aesthetic of the Independent Group

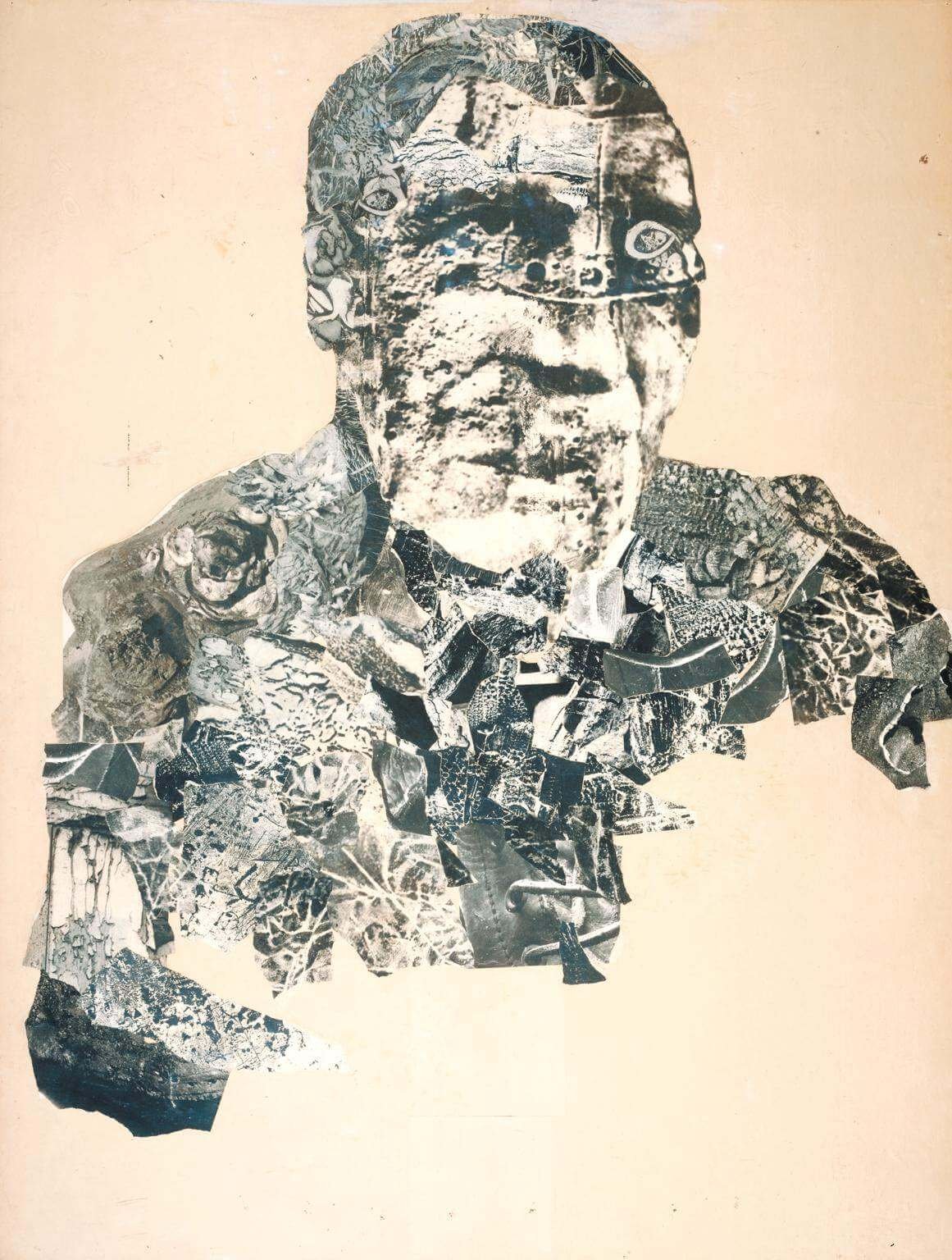

The Independent Group pioneered the use of collage as both an artistic and conceptual response to post-war reality. Through collecting, fragmenting, and reassembling visual material from mass media, the group’s artists critiqued consumerism and reshaped the aesthetics of modern British art.

Eduardo Paolozzi’s 1947 collage, I was a Rich Man’s Plaything, is recognized as the first artwork to use the word “pop.” This pivotal piece marked the birth of Pop Art, showcasing how commercial images could be repurposed into powerful visual critique.

Their “aesthetics of plenty” embraced the imagery of advertising, cinema, and consumer products, while exposing the emptiness beneath the surface. The Independent Group’s collage art, collaborative exhibitions, and architectural innovation continue to influence contemporary artists, digital art, and visual storytelling in design and immersive installations.

Today, this legacy is alive in fields like post-internet art, street art, multimedia installations, and experiential design—all reflecting the Independent Group’s groundbreaking approach to visual culture.

Politics, Critique & Cultural Legacy

The Independent Group was not just artistic—it was intellectual and political. Members like Reyner Banham and the Smithsons critiqued national events like the 1951 Festival of Britain, which they saw as retrograde. They pushed for bold innovation in art and architecture, resisting nostalgia and embracing new technologies.

Their visual experiments, from collage to urban form, exposed tensions between consumption and meaning, spectacle and critique. The Independent Group’s subversive embrace of mass media, pop culture, and satire heavily influenced British Pop Art and laid the groundwork for postmodernism in contemporary art and cultural theory.

Their influence rippled through later movements—from the Young British Artists (YBAs) of the 1990s like Damien Hirst to 21st-century installation artists and digital creators.

Iconic Exhibitions & Group Collaboration

The Independent Group’s exhibitions were vital to their cultural impact. Shows like Parallel of Art and Life (1953), Collages and Objects (1954), and Man, Machine and Motion (1955) demonstrated their vision. These collaborative art exhibitions integrated collage, photography, sculpture, and industrial design, bridging the gap between contemporary art and mass-produced aesthetics.

Their landmark exhibition This Is Tomorrow (1956) at the Whitechapel Gallery brought together teams of artists, architects, and designers to create immersive environments using jukeboxes, neon lights, Pop Art posters, and found materials. Group Six’s Patio and Pavilion combined sculpture, architecture, and conceptual art in ways that presaged the rise of installation art and multimedia environments.

Critics and historians regard This Is Tomorrow as the starting point for British Pop Art, a major turning point in the history of modern art and visual culture in Britain.

Key Figures & Intellectual Impact

-

Richard Hamilton became a central voice in British Pop Art, notably through his influential collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (1956). His later teaching at the Royal College of Art cemented his influence on subsequent generations .

-

Eduardo Paolozzi contributed bold, vibrant prints and sculptures drawing on consumer imagery, shaping the materiality of modern sculpture.

-

Lawrence Alloway championed the inclusion of mass culture in critical discourse and coined the term “Pop Art,” bridging visual art and cultural theory.

-

Reyner Banham critiqued modernist architecture and promoted New Brutalism, applying the Group’s aesthetic strategies to built form.

-

Alison and Peter Smithson brought the ethos of the Independent Group to architectural practice. Their raw, truth‑to‑materials designs, aligned with New Brutalism, emphasized honesty and function over decoration.

-

Nigel Henderson, John McHale, and William Turnbull broadened the stylistic range of the Group—from gritty photo‑collage to abstract sculpture. McHale and Alloway’s 1954 Collages and Objects exhibition established the “found‑object” aesthetic in a collaborative context.

Contemporary Resonance and Continuing Legacy

Today, the legacy of the Independent Group is more relevant than ever. Their work is frequently revisited in major art exhibitions, retrospectives, and academic discourse. The Tate, Buffalo AKG Art Museum, and Whitechapel Gallery continue to showcase their innovations in modern art, Pop Art, and post-war visual culture.

The 2024 revisiting of This Is Tomorrow, along with recent ICA programs, has renewed attention on their contributions to collage, mass media art, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Their legacy inspires today’s artists, designers, curators, and scholars exploring themes of media saturation, globalization, and identity in contemporary art.

Through digital art and socially engaged practice, their vision of collaborative, cross-genre, visually abundant art lives on in today’s most cutting-edge work.

Conclusion

The Independent Group stands as a transformative force in the evolution of British and global contemporary art, Pop Art, and architecture. Their radical blend of consumer imagery, mass media critique, collage, and interdisciplinary collaboration helped shape modern art as we know it.

Their enduring relevance is visible across visual culture, from academic theory to Instagram-era art, from museum walls to public space interventions. The Independent Group’s aesthetics of plenty continue to provide a vital lens through which artists, curators, and architects rethink creativity in an ever-changing cultural landscape.